The

“Morning Star of the Reformation,” John Wycliffe (ca. 1320-1384) was a

contemporary of the “Babylonish Captivity,” Geoffrey Chaucer, and John of

Gaunt. In his recoil from the spiritual apathy and moral degeneracy of the clergy,

Wycliffe was thrust into the limelight as an opponent to the papacy. The

readiest key to Wycliffe’s career is to be found in the conviction, a

conviction which grew deeper as life went on, that the Papal claims are

incompatible with what he felt to be the moral truth of things, incompatible

with his instinct of patriotism, and finally, with the paramount authority of

the inspired Book which was his spiritual Great Charter. He seems to have

become one of the king’s chaplains about 1366, and became a doctor of theology

in 1372, before being sent to

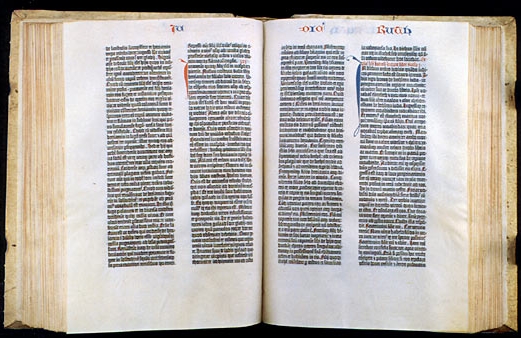

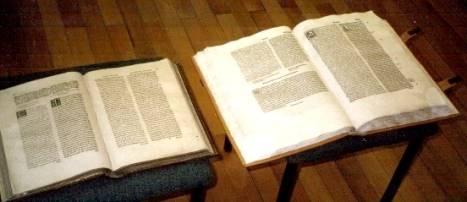

Wycliffe's Bible Tyndale's

1536 New Testament

Wycliffe

cast aside his dry scholastic Latin to appeal to the English people at large in

their common language. That appeal was primarily through the Lollards, an order

of itinerant preachers, “poor priests,” who went throughout the countryside

preaching, reading, and teaching the English Bible. Toward the close of the

fourteenth century the great Wycliffite translations of the Bible were made.

The New Testament (1380) and Old Testament (1388) translations

associated with him formed a new epoch in the history of the Bible in

The Catholic Reformation (ca. 100 years before Prot. Reformation) was about the 1) Internalization of Christianity, and 2) Intoleration of Abuses.

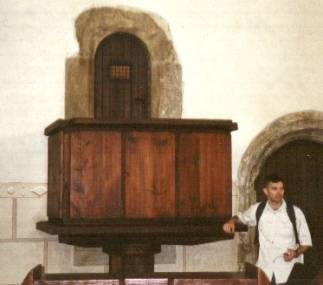

As a student of Wyclyffe, John Hus began to understand the supremacy of scripture (1400). Bethlehem Church is where John Foxe asserted Huss "seemed rather willing to teach the Gospel of Christ than the traditions of bishops," and was accused of being a heretic (John Foxe, Foxe's Book of Martyrs, (Springdale, Pennsylvania: Whitaker House, 1981), pp. 90-91).

John Hus,

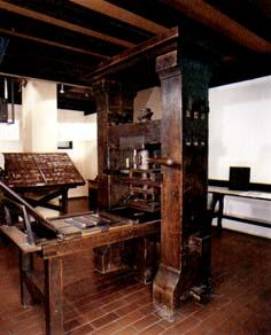

Johann

Gutenberg,

Gutenberg Bible

One

of the most important inventions that brought the world out of it's long sleep

was the printing press. Johann Gutenberg (1397-1468) has

been long credited with the invention of a method of printing from movable

type, including the use of metal molds and alloys, a special press, and

oil-based inks. His method (while refined and further mechanized)

remained the principal means of printing until the late 20th century. He

printed the first book, which happened to be the Bible.

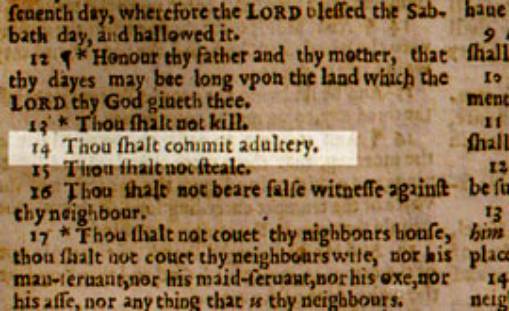

Excerpt from the "Wicked

Bible"

A

series of events, beginning with a power struggle, kicked off the English

reformation. Henry VIII (1509) wanted a

break from Papal authority, not a Protestant Reformation. It was not that King Henry VIII had a change

of conscience regarding publishing the Bible in English. His motives were more

sinister. But the Lord sometimes uses

the evil intentions of men to bring about His glory. King Henry VIII had, in

fact, requested that the Pope permit him to divorce his wife (Catherine, with

whom he had Mary, who would later become Queen) and marry his mistress (Anne

Boleyn, with whom he would later have

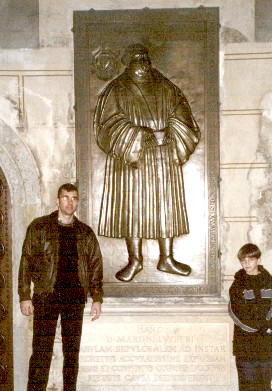

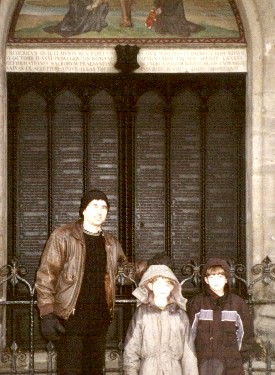

Martin

Luther, having read Romans 1:17,

realized that no one could please God without faith alone--sola fide.

Having posted his Ninety-Five Theses on the door at

Marin

Luther,

As the humanities flourished, Desiderius Erasmus and others began to assemble New Testament manuscripts in order to develop a standardized Greek New Testament.

Erasmus'

GNT (1516, first published) and Ximenes' GNT

(1514, first printed), Institute for New Testament Textual

Research,

Luther later translated the Greek New Testament into his native language, German. This marked the first time a translation was made from the originals into the language of the common people since Jerome's translation to Latin (400 CE). Luther, having learned New Testament Greek from his friend Melanchthon, accomplished this task while hiding out at Wartburg, where he remained until 1522. He used Erasmus' GNT.

Ulrich

Zwingli led the reformation in

Note: While I make every effort to produce an

error-free document, errors occasionally creep in. I would appreciate you bringing

any to my attention so that I may make the necessary corrections.

Post-Reformation/Anabaptist Church History